https://github.com/saskia-rr/Evaluating-Constitutions

GitHub - saskia-rr/Evaluating-Constitutions

Contribute to saskia-rr/Evaluating-Constitutions development by creating an account on GitHub.

github.com

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2411.10168

The growing capabilities of large language models (LLMs) have led to their use as substitutes for human feedback for training and assessing other LLMs.

These methods often rely on 'constitutions', written guidelines which a critic model uses to provide feedback and improve generations.

We investigate how the choice of constitution affects feedback quality by using four different constitutions to improve patient-centered communication in medical interviews.

In pairwise comparisons conducted by 215 human raters, we found that detailed constitutions led to better results regarding emotive qualities.

However, none of the constitutions outperformed the baseline in learning more practically-oriented skills related to information gathering and provision.

Our findings indicate that while detailed constitutions should be prioritised, there are possible limitations to the effectiveness of AI feedback as a reward signal in certain areas.

1 Introduction

In current practice, pretrained large language models (LLMs) are adapted with feedback learning to encode specific desirable abilities, especially conversational behaviours and safety alignment [1, 2].

Learning from human feedback (e.g. RLHF) has been generally seen as the gold standard [3], but this method can be prohibitively expensive, leading to the use of synthetic feedback paradigms such as 'LLM as a Judge' [4] and 'Constitutional AI' [2].

Using LLM-generated feedback involves asking a model to self-critique and generate revisions of previous work it has produced, typically based on a set of rules or 'constitution' [2].

Since these constitutions replace human interpretations of complex concepts and behaviours, it is important to consider how the content of the constitution impacts the results of the method.

While previous work has shown that more specific constitutions are only marginally better than high-level goals in the case of broad values like 'helpfulness/harmlessness' [5], we are additionally interested how well constitutions can shape specific socio-communicative behaviours.

We draw on the case of medical practice, where principles for 'patient-centered communication' [6] have been operationalised with detailed frameworks for the training and assessment of medical practitioners.

Medical uses of LLMs are an active area of study [7, 8, 9, 10, 11], including the AIME model [12], which incorporates an AI feedback learning approach to train social behaviours such as communication.

We expand upon this work by exploring how different constitutions effect the ultimate quality of model generations.

We compare four different test scenarios based on two different established clinical guidelines, broad role descriptions, and feedback in the absence of a constitution.

We use iterative in-context learning to guide model generations based upon these constitutions, and then rate the quality of the final outputs in comparisons judged by humans.

We find that using a more detailed constitution is more effective for improving patient-centered communication skills along emotive dimensions, but find no difference or worse performance along the more practically-oriented dimensions.

2 Methods

2.1 In-context Learning with AI Feedback

The core element of reinforcement learning with AI feedback is an iterative process of in-context learning, through which constitution-based feedback is used to create preferred model outputs [2, 12].

These outputs are subsequently used for fine-tuning, and the process can be repeated, but the primary impact of the constitutions takes place through this in-context learning.

As such, we focus exclusively on the improvement of dialogues via in-context learning, with the expectation that better results in this portion of training would extend to better overall results.

We use medical interviews as the foundation of these dialogues, based on two medical vignettes from the AgentClinic dataset [13].

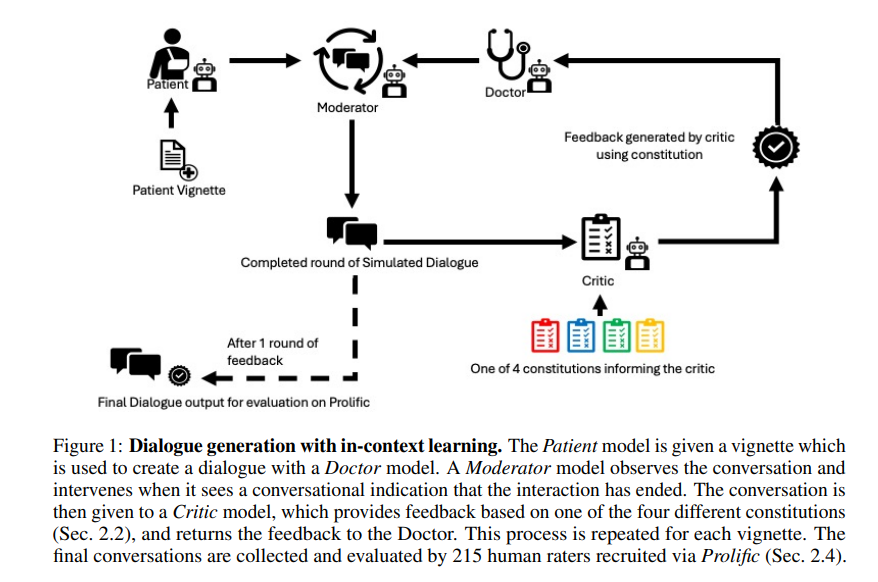

To perform in-context learning, we create an iterative loop using four different LLM agents, modelled after Fu et al. [14], Tu et al. [12] and Bai et al. [2].

Each agent is an instance of Claude 3.5 Sonnet, queried via API.

These roles (see Figure 1) include: Patient, acting as a patient based on an AgentClinic vignette [13] in the system prompt which contains information about the symptoms and demographics of a patient 'character'; Doctor, who collects information and reaches a diagnosis for the 'patient'; Moderator, responsible for determining when the conversation between Doctor and Patient agent has ended; and Critic, who provides feedback to the Doctor agent based on a chosen constitution.

After the critic agent has given one round of feedback, and the patient and doctor have completed two conversations, we record the final conversation as the output to be assessed.

We use this process to generate one complete conversation per constitution for each of the two vignettes.

For fairness between constitutions, we excluded and replaced conversations where the patient model failed to follow the vignette by hallucinating symptoms or not acting as a patient.

Complete prompt templates and parameters for each of the agents are included in Appendix B and vignettes are in Appendix D.

2.2 Constitutions

We compare four constitutions, as described below (for the full text, see Appendix A).

1) Best Practices, based on the widely-used 'Patient-Centered Communication' framework established by King et al. [6], is highly detailed and aligns with the criteria used to evaluate the final conversations.

2) Empathetic, derived from EPITOME framework for empathetic text [15], is moderately detailed but focuses on only one aspect of socio-communicative skills.

3) Doctor, inspired by Kundu et al. [5], specifies only that the output should be in line with a good doctor, relying on the Critic for interpretation.

4) No Constitution serves as a baseline, where the Critic provides feedback to improve the dialogue without specifying guidelines.

2.3 Evaluation Framework

The final conversations are compared according to the six categories of the 'Patient-Centered Communication' framework [6], with the relevant questions adapted from Reeve et al. [16] and Moser et al. [17].

The categories are shown in Table 1.

For each dimension, we collect pairwise ratings between the generated conversations.

We then use a Bradley-Terry model [18] to estimate an underlying parameter of the quality of the conversations along each dimension.

2.4 Human Evaluation

To evaluate the final conversations, we recruited 215 human raters from Prolific.

Each participant is presented with two randomly selected conversations based on different constitutions, and asked to make comparisons between them according to the 'Patient-Centered Communication' framework as well as providing a holistic preference.

Participants repeat this twice, seeing one conversation for each constitution, but not all six possible pairings.

Participants are paid £2.75 for an average of 13 minutes of time.

Due to the length of the conversations being compared, we required participants to answer one comprehension check question per conversation, and we excluded 2 participants who failed more than once.

We did not exclude participants who skipped other questions, leading to slight imbalances between the number of ratings per question and pair.

We excluded 16 participants who started but did not complete the survey, an attrition rate of 7%.

This research was pre-approved and carried out in line with institutional ethics approval (reference number OII_C1A_24_203).

3 Results

In Figure 2, we show the rate at which the conversations generated according to each constitution are preferred to the others for each dimension of evaluation, alongside the estimated parameters for a Bradley-Terry model.

The Best Practices constitution is preferred to the other constitutions for 'Fostering the Relationship', 'Decision Making', and 'Responding to Emotions'.

There is not a clear difference between the constitutions for 'Gathering' and 'Providing Information'.

For 'Enabling treatment behaviour', the Best Practices constitution leads to worse results than the non-specific doctor constitution and the empty constitution.

When holistically selecting a most-preferred constitution, there was not a clear pattern across participants, though many participants indicated a dislike of verbose or overly emotive responses even when rating them as more 'empathetic'.

4 Discussion

For the emotionally-oriented dimensions (Fostering the Relationship, Decision Making, and Responding to Emotions) of patient-centered communication, we found that the most specific constitution led to the most human-preferred dialogues.

This is consistent with previous work comparing constitutions in the case of 'harmlessness' [5], and indicates that efforts to create detailed constitutions are likely to improve the outcomes of AI feedback methods.

This is also supported by the poor performance of the generic "Doctor" constitution, which is indistinguishable from the "No constitution" treatment in all six dimensions, and the success of the 'Empathy' constitution in 'Responding to Emotions', but not the other categories.

We do not see the same improvements for the more practically-oriented dimensions, where the LLM needs to manage information exchange with the patient.

These type of behaviours may be more difficult for language models to judge and learn, as they involve planning and theory of mind, while emotional signals may be imitated by adding sensitive-sounding phrases [7].

We also note that qualitative feedback from participants who did not like the verbosity of the models reveals that aspects of the reward function such as sentence length may be intuitive to humans but not LLMs [12], and that human preferences remain difficult to measure well.

In this study, we focused on comparing four specific constitutions in the case of patient-centered communication in medicine.

For each constitution, we used only two dialogues, limiting the generalisability.

This is partially compensated by having six different axes of comparison, showing that the dialogues are improved in several, but not all cases.

While we argue that in-context learning is the key mechanism for RLAIF, fine-tuning based on a collection of examples would allow a model to learn behaviours which are not present in every example.

As such, a wide range of small improvements may be aggregated to achieve better results than what we observe in a single interaction with in-context learning.